Omar Di Felice after Antarctica Unlimited

It’s hard to imagine Antarctica in its entirety. We can only truly appreciate its location by looking at a globe, because it truly is a World at the End of the World: a kind of imperceptible closeness between continents – South America, Africa and Oceania – that appear extremely far away on a normal world map.

We met with Omar Di Felice who talked to us about his incredible experience in Antarctica.

“It is an almost unimaginably anomalous place. Completely white, cloaked in unreal silence – like a gigantic, completely sound-proofed room – and where, incredibly, the wind always blows in the opposite direction to the direction of travel. The katabatic winds form in the atmosphere and then rush down very strongly from the top down. In Antarctica, even the wind is different from how we perceive it in the rest of the world. It is neither favourable nor unfavourable. It’s downslope wind. You’re constantly at the mercy of this mighty glacial gale which rips everything right out of your hands. In my case, everything I had on the sled that I was towing with my fat bike was indispensable, and to see these essentials being blown away by the wind – this happened to my tent, which luckily, almost by miracle, I managed to retrieve – seriously jeopardised the expected duration and outcome of my adventure.”

For Omar Di Felice, not being able to complete the route originally planned for Antarctica Unlimited is by no means a source of anguish or distress. Far from it: it is confirmation of what Omar has always believed. Namely, that nature cannot be controlled by man at all.

“In Antarctica, nature rules supreme. If katabatic winds are blowing at 80 kilometres per hour, it is unimaginable to try to get on the saddle and proceed along the pack ice. You spend days on end in your tent waiting for the wind to die down, and when it does, your planned road map is shattered, only to be broken again when the wind speed picks up again. If the intensity of the winds starts to dwindle, you could get trapped by the White Out. Suddenly everything becomes white and visibility is reduced to zero – so much so that you can't even see the screen on your mobile phone – and, in those conditions, you feel completely disoriented. Luckily, my satellite showed me the way, but cycling was impossible because I couldn't see anything. I couldn’t even keep my balance on my bike. It was like trying to move through an endless cloud.”

“To explain this feeling a little better: cycling in Antarctica is not like the Stelvio or on any other famous mountain pass. As bad as the weather gets, sooner or later it does improve and you can climb up. If the worse comes to the worst, you have to wait two or three days, and then, covering up properly, you can set off.

In Antarctica, things are dramatically different: you can sit still for a week or two because the katabatic winds continue to blow relentlessly. You sit still inside a tent and haven’t got a clue when all that blowing will end.

I often thought about those first polar explorers, who faced Antarctica with equipment and materials dating back more than a hundred years: Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton. They were completely at the mercy of nature, far more than I was. However, nature prevailed this time just as it did back then.

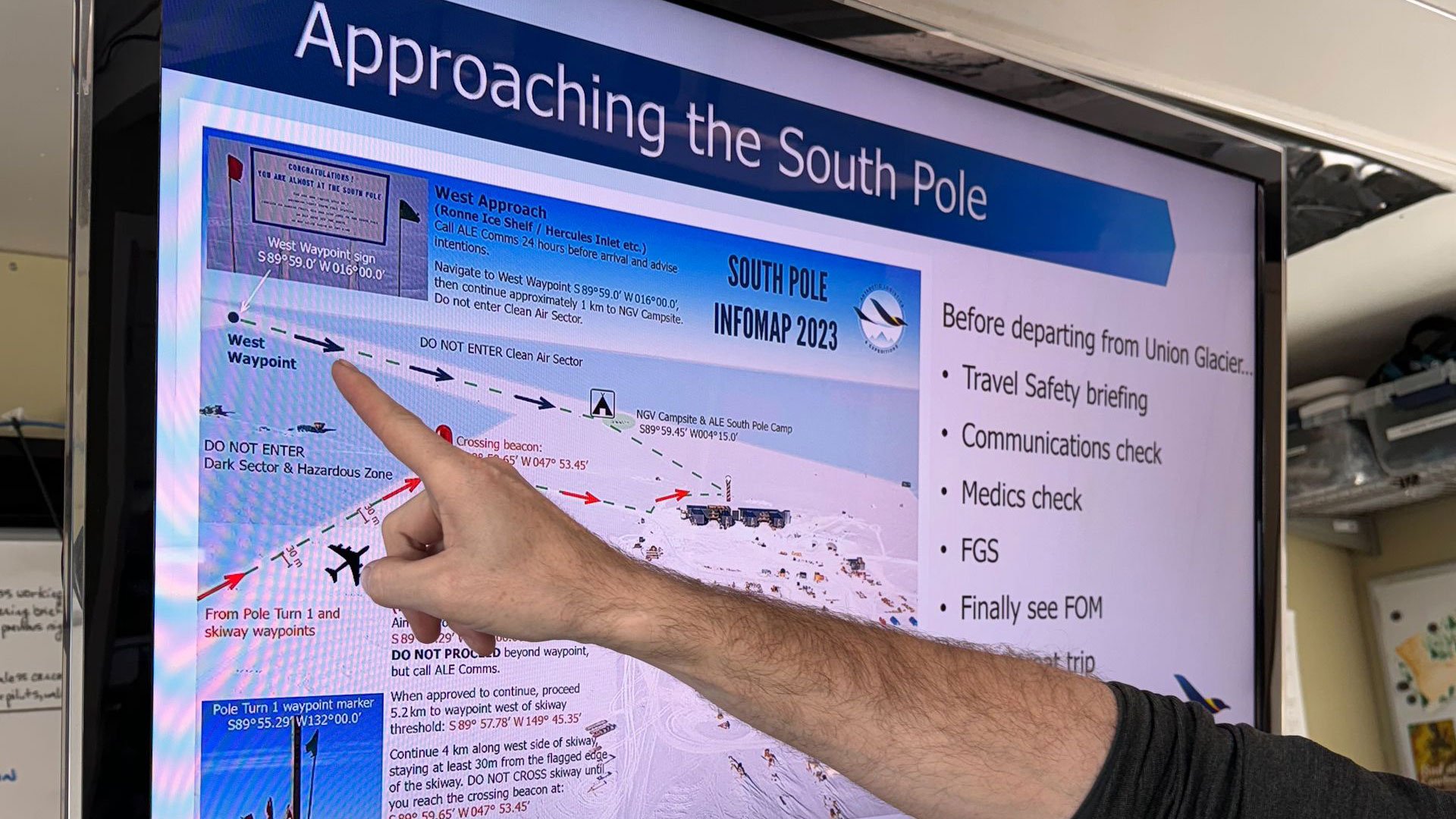

At the end of the day, even with the state-of-the-art equipment and instruments I had with me, I had to give up and get rescued near the Thiels Mountains. Any other decision would have endangered both my safety and the safety of those who were supposed to come and get me. Nevertheless, I’m happy. I stayed in Antarctica 51 days in direct contact with unbridled nature. I’m not interested in how many kilometres I covered, nor in how many I was supposed to cover. I don’t even care about not reaching the geographical South Pole. I did exactly what nature allowed me to do.”

It is inevitable that the interviewer, at some point during the interview, asks Omar Di Felice the fateful question: “Why do you do these things? Why do you venture into these endeavours?”

“It was an enlightenment that came to me twenty years ago. I realised then that the racing bike was limited to road races: the Giro d’Italia, the Tour de France, the classics we all know and love. It had nothing to do with the dimension we now call Ultracycling. Those who tried their luck with these long races were bicycle tourists from Northern Europe, who could be spotted in Italy pedalling in their sandals and loaded with backpacks perilously perched on top of their bicycles. That’s when I asked myself: “Could it be that the racing bicycle only has a competitive value and cannot have other values?” Indeed, twenty years ago, I began to give some thought to the then imponderable project that brought us to the polar pack today.

But, in actual fact, it is not even a question of imagining and putting into practice adventures and endeavours. The truth is, in fact, that in Antarctica, the bicycle is a means of transport with an extremely limited usefulness: the best way to get around is clearly on skis; nevertheless, what I wanted to demonstrate was that even in Antarctica, this wonderful object can find a dimension. It can get as far as Everest base camp, cross the Gobi Desert and eventually reach the South Pole as well. It's definitely not the best mode of transport for those environments, but it can still get there. I even expect that one day a cosmonaut will ride on some otherworldly ground on some sort of fat bike and start cycling. It is clear that it is not a suitable tool for that territory, but the bicycle is such a ductile and extraordinary invention that it can go anywhere.

This is the ultimate meaning of my adventures. To take this object places no one would expect, because its possibilities are unexpected and, I think, unlimited.”

It is also inevitable that another question springs to mind: “And now, after Antarctica, what kind of adventures can you imagine?”

“I understand it’s hard to think that after these 50 days on the Antarctic ice pack there are still limits to explore. And yet this is exactly the case. Over the next few months, I will be touring Italy to meet students and fans and share my experience with them. I also want to put myself to the test again, investigating and exploring my possibilities further.

Because, after Antarctica Unlimited, I can say that I know myself a little better: I observed some of my physical and mental limitations that I had not yet considered. This is precisely what I want to continue doing and I am already considering which kind of environment to attempt to get to know myself even better.”

Related stories

Marche trail vibes/memories

Antarctica Unlimited: Omar Di Felice's Great Antarctic Dream

Southward

Georgia and the Greater Caucasus: Wiebke Lühmann's latest bikepacking adventure

Omar Di Felice triumphs in the most legendary Ultra Cycling race: the 2023 Trans Am Bike Race

Newsletter

Fill in the form below for updates on all that's new in the Wilier Triestina world, with plenty of content: product news, technical insights, professional teams, fairs and events, ambassadors, promotions and offers, all arriving in your email box. And if you no longer want to receive news from us, you can unsubscribe at any time.